REST Misconceptions Part 3 - More Than Links

In the fourth part of my REST series I will expand the idea of links. Links are just a stepping stone no matter how important.

Simple links aren’t enough for the client to interact with the server. After all how is it going to know when to POST

and when to PUT or what are the required parameters and request bodies. This is where affordances come into play. It

means that the server should include all information the client needs. Just as defined by the self-descriptive constraint.

In this series:

- Introduction

- Misuse of URIs

- Not linked enough

- More than links

- Resources are application state

- REST “documentation”

- Versioning

Affordances

The word affordances is derived from the verb to afford and simply means what a person (or client) can and cannot do. Affordances are a very important aspect of a REST API, because they are precisely what sets it apart from RPC-style APIs. In an RPC style architecture, the client must know up-front what the interface allows. That information can be provided in the form of SOAP’s WSDL documents, CORBA’s IDLs or exposed via a RMI Registry. It is then used by the client to generate programming objects used to access the remote API as if it was local.

Problems arise when the API evolves, because old clients are at risk of breaking until they are updated to work with a new

version of the API. This is not how the Web works. Human-browsable HTML document encapsulate all possible interactions

in the form of links (<a>) and forms (<form>). When the API of any given web page changes, it’s not necessary to

perform any action. For example when a new parameter is required to perform an action, the <form> contained within the

page simply displays an additional <input> or similar field.

Affordances and REST

The web browser example above is very common among the proponents of REST. The web can work this way thanks to the Hypertext

Markup Language or HTML. More precisely, it works because disparate parties agreed upon the crucial technical details so

that any client understanding HTML document could operate in a similar manner. There may have been weird, non-standard

quirks like the infamous <marquee> element, vast differences in Javascript and ongoing trouble with the behaviour and

appearance of <input> and friends. The forms and links however have been consistent (I think?), which

means that a web page from 1998 will likely look old and too colorful and maybe very ugly ![]() , but it will still work just

fine in terms of what you can click to go to other places.

, but it will still work just

fine in terms of what you can click to go to other places.

REST aspires to bring such timeless goodness to the way developers and users (with the help of clients) use their APIs.

The human-facing Web works because there is the text/html media type. To work in similar fashion a REST API needs

a media type rich enough so that servers can provide the client with all the information they need to make requests. Here’s

what Roy T. Fielding wrote on his blog.

A REST API should spend almost all of its descriptive effort in defining the media type(s) used for representing resources and driving application state, or in defining extended relation names and/or hypertext-enabled mark-up for existing standard media types. Any effort spent describing what methods to use on what URIs of interest should be entirely defined within the scope of the processing rules for a media type (and, in most cases, already defined by existing media types). [Failure here implies that out-of-band information is driving interaction instead of hypertext.]

It means that a response must contain all information about how the client interacts with the server. This includes the shared understanding of the structure and meaning of the media type.

Why do I need hypermedia?

As with links, which decouple client’s from URI structures, rich hypermedia description makes it possible to decouple the client from the server thus insulating the client against changes in the server’s responses and input requirements. How many time have you written JavaScript code, which checks the state of an object, before calling the server? For example a blogging platform could disallow deleting of posts in certain conditions:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Or what about creating and updating resources? Updating is simple, usually it would be a PUT

1

| |

Creating on the other hand can be modelled in a number of ways. It can be a POST to a collection

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

But it could just as well be a PUT to a identifier prepared by the server. Or maybe the client should be allowed to mint

a URI somehow and PUT the representation there?

If you ever find yourself implementing the client in a way that it has to know such details about the server’s requirements, it means that you are violating the hypermedia constraint.

DIY hypermedia

As we’ve established, to be fully RESTful a media type must be used, which allows for a rich description of the possible actions. That description is called hypermedia controls. Instead of implementing clients against specific URI structures or conventions, client should expect named actions.

For example the Twitter API could attach a retweet relation to a single tweet. Such relations are similar to links.

Just as the client can expect a specific link it wants to follow, it could also expect an action or operation relation.

The difference is that links are simple URI (or templates), whereas actions require additional details. There are a number

of aspects, which a media type can describe about a an action. From a pragmatic standpoint, it is possible to just incrementally

extend resource representations as to remove the out-of-band knowledge the client requires.

1

| |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

I’ve just invented an application/vnd.warpdrive+json media type, which includes an array of possible actions and details

about them. In this example I’m instructing the client how to add a movie to favourites. Depending on my needs I would

extend it with more details:

- accepted and returned media types,

- contracts of request/response bodies,

- input datatype constraints (ranges, etc),

- URI templates,

- more.

All these details would be defined by the media type itself and implemented in a reusable library. All the API client

needs to know is the addToFavourites relation name.

Hypermedia media types

Or is it just hypermedia types? Anyway, there are a ton of media type, which to some extent satisfy the needs of a hypermedia constraints: HAL, SIREN, Hydra, Collection+JSON, Atom, MASON, NARWHL. They are not equally powerful, but all have a great advantage over do-it-yourself hypermedia type: they are out there and understood by existing clients and tools. So unless you’re creating a dedicated API for a single client application or an internal API for an organization it is worth adopting any existing media type. Doing otherwise would require a big investment in client libraries, so that clients can be built, which can interact with your API. As I wrote above there is a lot to consider when choosing a hypermedia type. I’ve come across two interesting approaches.

Hypermedia Maturity Model

I wrote before about two post, where Arnaud Lauret aka. API Handyman discussed what kind of descriptive power a good hypermedia type should have:

- Include links to other resources

- Describe possible actions

- Describe how to execute those actions

- Inform why some actions are unavailable

- Describe complex workflows

H-Factor

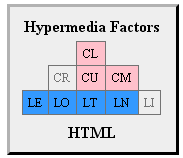

A similar, albeit a little earlier model for measuring the hypedmedianess of a media type is Mike Amundsen’s H-Factor, or hypermedia factors, which defines a different set of features a media type can have:

- Link Support

- [LE] Embedding links

- [LO] Outbound links

- [LT] Templated queries

- [LN] Non-Idempotent updates

- [LI] Idempotent updates

- Control Data Support

- [CR] Control data for read requests

- [CU] Control data for update requests

- [CM] Control data for interface methods

- [CL] Control data for links

They are displayed in the form of cute pyramids. Here’s the example of H-Factor for HTML: