Declarative UI "Routing" With Web Components

For a long time now W3C has been working on Web Components, the groundbreaking specification, which will dramatically change the way web applications are created. Google’s own Eric Bidelman calls it a Tectonic Shift and for good reason.

In my previous post I proposed a novel way for managing the application state of RESTful clients - that is clients of RESTful services. To recap, the idea is that the user interface should be rendered first and foremost based on the resource returned by the server rather. I propose that is an alternative to client-side URL routing.

Web Components

I will be showing examples written with custom elements - part of an upcoming W3C standard, which will allow creating custom HTML elements. Those custom elements act like the standard HTML tags, accepting attributes and exposing methods and firing events. Altogether the Web Components specification will define four complementary standards:

- Shadow DOM - allowing encapsulation and separation of markup and CSS

- Templates - for defining reusable portions HTML (not just text)

- Imports - so that elements can be loaded on demand

- Custom elements - to enrich HTML with custom, semantically significant elements

Combined, though each could be used separately if needed, these standards empower web developers to create web applications in ways unimagined before. For example, there is a custom google maps element, which makes adding a map to your page as simple as shown below.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | |

No boilerplate JavaScript that would traditionally obscure intent. And it would be so much easier to replace Google map with Yandex, Open Street Map, Leaflet or other from custom elements.

Note The webcomponents.js is a polyfill currently required for browsers other than Chrome and Opera.

You can find dozens more components on component kitchen, customelements.io and some more experiments by google.

I really, really love how Web Components turn the traditional <div><soup>

into meaningful code. They are a tool for creating Domain-Specific Language for HTML.

Routing with Custom Elements

There is a neat component, which implements traditional URL routing as a custom <app-router> element.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

It supports imported and inline templates, binding to route parameters and all other features found in all-javascript routers.

It is still URL-routing though. Also the approach to handle routing and browser history in one component violates the single responsibility principle IMO.

Linked Data to the rescue

The <app-router> component is a great base, which can be adapted to handle REST models. Below is my idea, which I have

been experimenting with by modifying the app-router’s code, thus retaining the template loading functionality and events.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Unlike <app-router> I think that <ld-presenter> should only handle selecting a view to honour the Single

Responsibility Principle. History could be handled by another custom element created for that specific task:

1

| |

Dropping the above anywhere in the page would automatically change the page URL (by using hashes or HTML5 history) whenever the model changes.

So where is the model actually? And how is it retrieved?

The approach to build UI based on a model has an important implication - it has to be connected to some remote (RESTful)

data source. Because the <ld-presenter> is only responsible for handling UI changes, a separate object is needed to

retrieve the model.

Speaking of single responsibilities, the <ld-presenter> should probably work simply by being bound to the object displayed.

This would be achieved by setting a model attribute on the presenter’s node.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

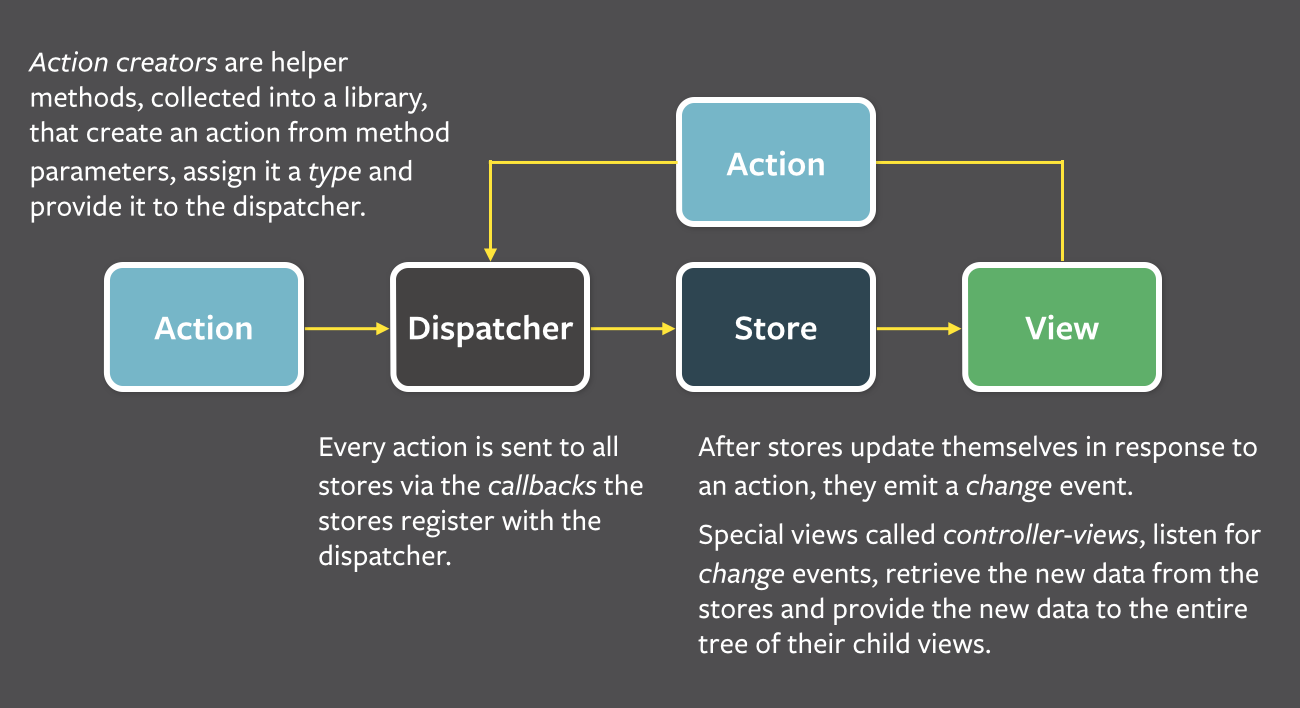

Either way the model must come from somewhere. For a complete solution the Flux pattern from Facebook can be used to achieve low coupling. Out of a number of solutions reflux appealed to me most, but the idea is similar regardless of the implementation. The idea behind Flux is that all communication should be unidirectional. The views fire actions, which are simply events. Those events are handled by stores. Stores are anything ranging from simple local storage to proxies for a remote service. When stores are ready they also signal changes via events to all listening views so that the can be updated.

What’s important, is that stores and views never communicate directly. This way it is easier to keep things decoupled and synchronized. Note that in Reflux’s case there is no dispatcher. Stores listen directly to actions.

Using Reflux to handle a Linked Data API

Because in Linked Data any identifier is a URI, readible links can be rendered simply as an anchor <a>. Let’s take a

simple JSON-LD model of a person (@context ignored for brevity):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

That model could be displayed using the template below (think Polymer/mustache syntax)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

The link will by default navigate the browser to a new address, so the click event must be handled to prevent that from happening. Instead an action will be triggered. Below is how that could work with Reflux and requirejs. First we define the actions.

1 2 3 4 5 | |

We fire the action when the link is clicked.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

It is handled in a store. When that happens, a GET request is fired. After the request has been processed (JSON-LD here),

it is forwarded with the child action success.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | |

Lastly the navigation.success action is handled to update the ld-presenter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Rough edges

My current experiment I’ve implemented more or less follows this pattern but the <ld-presenter>

(there called <hydra-router>) is tied to the navigation actions, which means that anyone using such presenter is

automatically required to use Reflux. Real presenter should be independent from any third party components. Such

integration could be achieved with minimal javascript code. Preferably by extending the custom element or

inside an angular directive, etc.

Also with a hard dependency on navigation action, any instance of the presenter element in DOM would every time react to the action being fired. This may be less than ideal when multiple and maybe nested presenters are used on a page. In a real app there could be multiple model stores for various parts of the UI like main menu or master-detail kind of view.